Creedmoor Elementary School of the Arts Free and Reduced Lunch

Executive Summary

- In 2010, Congress reformed the nutritional standards of the National School Lunch Programme (NSLP) and the School Breakfast Program (SBP) later on evidence showed that the meals were contributing to the childhood obesity epidemic.

- Following implementation of the new nutritional standards, show indicates these programs—particularly the SBP—may meliorate nutritional intake and reduce food insecurity and obesity, particularly amongst low-income children, with estimates of obesity reduction ranging from none to as loftier as 47 percent.

- There is stronger evidence that these programs improve educational functioning, with increased participation improving test scores by as much every bit forty percent amidst poor students; this correlation appears to have increased equally the nutritional quality of the meals improved.

- As the strongest evidence for positive furnishings on both wellness and teaching stalk from the SBP, which has a participation rate roughly one-half that of the NSLP, efforts to ameliorate SBP participation by making the program more than readily bachelor and providing students more fourth dimension to eat may yield additional gains.

Background and Plan Context

Roughly 60 percent of American schoolchildren receive schoolhouse-provided meals each day through the National School Tiffin Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP). Families at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) are eligible for costless meals, while those between 130 and 185 percent are eligible for reduced-price meals.

In 2010, afterwards years of ascension childhood obesity rates, Congress enacted the Salubrious, Hunger-Free Kids Act, which significantly reformed the nutritional standards of the NSLP and the SBP. Following implementation of these reforms, Healthy Eating Index (HEI) scores increased from 58 per centum to 82 percent for the NSLP and from 50 percent to 71 per centum for the SBP.[i] Prior to the reforms, studies suggested that these programs, specially the NSLP, had express and perchance even negative wellness benefits, including increasing obesity. Since, however, studies signal the programs may exist improving nutritional intake and weight, and reducing food insecurity by at least 3.8 percent and obesity past every bit much as 47 percent.[ii] Nonetheless, as of the 2017-2018 schoolhouse yr, one in five schoolhouse-age children were still considered obese and in 2019, 5.3 million children nonetheless faced nutrient insecurity.[iii]

Improving the nutritional content of these programs improves their educational effects, likewise. While educational benefits were establish prior to the nutritional reforms, research suggests that benefits are greater equally nutritional content improves. While the provision of meals of whatever sort motivated children to attend schoolhouse even before the reforms, greater nutrition is associated with improved ability to concentrate and higher test scores.

This newspaper summarizes the literature surrounding SBP and NSLP's impacts on health outcomes and educational attainment, both before and after the updated diet standards were adopted. Information technology should be noted, however, that implementation of these new standards has been gradual over the past decade, and some take yet to be full adopted, as explained here.

Health Impacts

Most of the studies assessing wellness impacts of the SBP and NSLP focus on similar variables: weight, obesity, trunk mass alphabetize (BMI), or adult height. Studies prove adult elevation to be highly positively correlated with childhood nutrition and health.[iv] Some studies more than simply assess nutrient consumption, using nutrition quality itself as a proxy for health. Other studies regard regular consumption of breakfast every bit either an indication of or reason for better health, equally numerous studies have shown the many benefits of regularly eating breakfast, such equally better mental function, greater vitamin and mineral intake, and better weight regulation.[5]

No/Negative Impacts

Studies finding either no impact or negative health impacts from the schoolhouse meal programs are erstwhile and acknowledge that other factors, such as income and a student's living environment as well as others discussed here and here, are at play, making it hard for the authors to truly isolate the programs' bear upon. For example, a 2009 written report found obesity rates were higher for participants of NSLP than for those who did not eat school-provided meals, despite having the same obesity rates when inbound kindergarten.[vi] The study suggests, however, that income rather than the schoolhouse-provided meals were to blame: All who were income-eligible for reduced-price lunches had a college likelihood of beingness obese, regardless of whether they really ate the meals. Farther, the additional calories consumed past students participating in the NSLP were all consumed at luncheon and enough to business relationship for the level of weight proceeds observed.[vii] Since the reforms implemented afterward this study sought to reduce calorie content, information technology is possible that higher calorie consumption for such children would no longer be found and thus the weight gain would besides disappear.

Ane long-term study from decades ago concluded that there are no long-term health impacts of these nutrition programs when considering developed height and BMI for participants, though the writer notes at that place may have been short-term impacts, including better cocky-perceptions of wellness.[eight] The author too speculates that the reason no health effects were found was because participants did non swallow whatever additional calories, contradicting the finding of the previous study.

Mixed Results: SBP More than Beneficial than the NSLP

Another 2009 study similarly constitute that participation in either schoolhouse meal program was generally associated with increased weight from kindergarten to third form and a greater likelihood of existence overweight, though in that location were differences in the effect of each program depending on whether the child entered kindergarten at a normal weight or overweight or obese.[ix] After bookkeeping for selection bias, the authors conclude that the SBP is non contributing to the increase in childhood obesity—and may even be beneficial in the fight to reduce obesity—while the NSLP likely is contributing to the increment in obesity.[x] The authors speculate the reason for the deviation is primarily related to the differences in the nutritional quality of the two meals—finding that schoolhouse lunches were much less probable to meet nutritional standards—as well equally the benefits of simply eating breakfast. Another written report from 2009 establish somewhat like results with a similar rationale: While in that location was no link between NSLP and students' body mass index, the SBP was associated with lower BMI, and the authors suggest the SBP may contribute to reduced obesity past encouraging students to swallow breakfast more regularly.[xi]

These findings follow those of a study from 2004 which showed the SBP improved diet quality not merely of students participating but also other members of their household; participation in the NSLP was non considered.[xii] Relative to times when school was not in session and the SBP was thus not available, participating students consumed fewer calories from fat, were less likely to have bereft consumption of fiber, Vitamin C, Vitamin Due east, or folate, and were more likely to come across the recommendations for potassium and iron intake.[xiii] Further, younger children and adults in the households of children participating in SBP had healthier diets and consumed less fat compared to when school was not in session, likely as a outcome of the power to shift resource allocation.[xiv]

A 2014 study regarding universal breakfast and the Breakfast-in-Classroom program constitute little bear witness of improvements to a child'due south daily nutritional intake and health across the broader population, though some improvements to health and behavior were seen in some highly disadvantaged subpopulations, including greater consumption of a nutritionally substantive breakfast, a decrease in the rate of overweight children, and an increased health index in loftier-poverty schools.[xv] Girls were constitute to consume more nutritional breakfasts and minority students had improved behavior.[xvi] Nevertheless, while at that place were more children taking breakfast at school under universal free breakfast policies, much of this increase was a result of children switching from home to school breakfast or consuming multiple meals each morning time rather than students receiving a meal they otherwise were not getting.[xvii]

Positive Impact

Other studies plant positive associations between the school food programs and health outcomes, primarily related to obesity. One of the nearly contempo studies examining survey information of 173,000 students found that while the updated nutrition standards had no bear upon on obesity overall, at that place were significant reductions in obesity amid children in poverty (those almost likely to consume schoolhouse meals).[xviii] The probability of obesity for such children decreased from 25 percent in 2012 to 21 percentage in 2018; based on the tendency from the prior x years, the study estimated that without the new nutrition standards, the probability of obesity amid poor children would take been 31 percent (or 47 per centum higher) in 2018.[nineteen]

In 2011, a report using National Wellness and Nutrition Test Survey information found evidence that the NSLP improved the health outcomes of children when accounting for differences between eligible and not-eligible children past reducing parental-reported poor health by at least iii.five pct points, nutrient insecurity by at least vii.six percentage points, and obesity past at least 9.iv percent points.[twenty] Another study using the aforementioned 2011 National Wellness and Nutrition Survey found that NSLP reduced obesity rates by 17 percent and led to a 29 percent reject in poor general health in its participants.[xxi]

A 2017 study found that universal free meals increased participation in schoolhouse tiffin programs amid both poor and non-poor students, similar to the findings of the study assessing universal breakfast programs, with twice the increase amid non-poor students equally poor students.[xxii] There was no bear witness that the programme led to an increase in average BMI, and some evidence suggested that participation in the school lunch program improved weight outcomes for non-poor students, contradicting earlier findings that NSLP led to weight gain.[xxiii] Because this written report was conducted after updated nutrition standards had been in result for several years, it supports the conclusion that the earlier studies' findings were affected past the nutritional quality of the meals.

Analysis from Deloitte estimates that the programs' ability to reduce food insecurity and BMI, and thus the prevalence of sure chronic conditions such equally diabetes and obesity, may contribute to fewer childhood hospitalizations.[xxiv]

Educational Impacts

Studies suggest good diet leads to better productivity and focus in school and thus greater educational attainment.[xxv] The effects of dietary factors on cognitive development and function are well established, and sure dietary choices can promote mental fitness, including better concentration and memory.[xxvi] Studies consistently find that school repast programs take a positive impact on educational outcomes.

Many studies focusing on the consumption (i.east., quantity of nutrient) of breakfast and luncheon suggest that access to these meals has sizable impacts on educational attainment. Providing breakfast in classrooms has been shown to improve considerateness and reduce disciplinary problems and tardiness.[xxvii] Research indicates these programs are a more price-effective mode to improve student learning and test scores than, for instance, developing smaller class sizes, which pose higher implementation costs.[xxviii]

The long-term written report mentioned earlier, which institute no health impacts from the NSLP, did detect a positive association with educational attainment (increasing by four months for women and a year for men).[xxix] The study's author attributes the educational proceeds to an increased incentive to attend schoolhouse every bit a result of the inexpensive or no-cost meal, and plant that the meal provided an even greater attendance incentive than mandatory attendance policies.[xxx] More contempo studies take similarly found school breakfast programs to be a motivating factor, reducing absenteeism, peculiarly among depression-income inner-city students.[xxxi] Other studies testify that those in food-insecure households are more probable to exist absent-minded from school, though this is primarily due to illness, and illness is more likely amidst children with nutritional deficiencies.[xxxii] This suggests that providing nutritionally rich meals is specially important.

A Brookings Institution study sought to decide the impact of the quality of school lunch diet on educational achievement by evaluating terminate-of-year exam scores at California public schools over five bookish years. This study did not specifically focus on NSLP just rather on the HEI of the meals provided by companies with which schools were contracting, focusing on the quality of food rather than caloric count. The results suggest that when students ate healthier lunches (i.eastward. those having higher HEI scores), their exam scores were, on boilerplate, 4 percentile points higher.[xxxiii] For those qualifying for NSLP programs, exam score increases were approximately xl percent greater.[xxxiv]

The previously mentioned 2017 study reviewing academic performance through test scores following the adoption of universal gratuitous tiffin programs in New York Urban center (where children received meals regardless of income) constitute that there were generally increases in test scores in math and English language arts for all students, though the academic improvements were greater for non-poor students than they were for poor students.[xxxv] Specifically, the authors estimate that the increment in lunches consumed leads to increased performance in math by the equivalent of seven to ten weeks of learning for non-poor students and three to 4 weeks for poor students; for English Language Arts, the increases represent half dozen to nine weeks and three to 4 weeks, respectively. The authors notation that the policy led to greater increases in participation in the school lunch program among non-poor students than poor students, perchance explaining the greater impact on performance amidst non-poor students.

The impact of these programs can also be assessed by examining teaching and wellness trends for students in the summertime when they practise non have access to these programs. Depression-income students face much more pregnant "summer slides" (learning loss) than peers, having a cumulative effect over fourth dimension that contributes to a widening achievement gap between low- and high-income students by the 5th grade.[xxxvi] A Deloitte report estimates that if all children receiving free or reduced-cost meals during the school yr had access to these meals in the summer, there could be as many as 81,600 more than kids who graduate high school each year.[xxxvii] These numbers underscore the importance of the programs during the schoolhouse twelvemonth, also.

Opportunities for Increased Participation

Given the positive health and educational benefits associated with school repast programs, particularly the SBP, gaps in participation offer opportunities for additional gains.

Children in families experiencing hunger are more likely to repeat a grade and receive special education resources.[xxxviii] School repast programs aim to eliminate the barrier of hunger, nonetheless at that place are nevertheless problems with participation. Of those eating school lunches, only 46 percent of students besides eligible for the SBP participated in it, according to a written report from 2011.[xxxix] While SBP participation has been steadily increasing, in that location are notwithstanding roughly just 60 percent as many students receiving a gratuitous breakfast equally a free lunch.[xl]

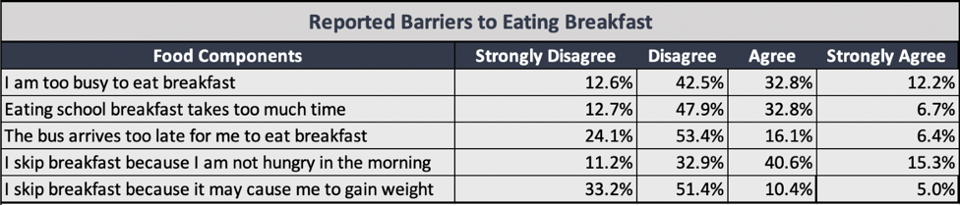

Further, overall increases in participation mask differences among historic period groups and races. The number of students consuming breakfast decreased dramatically with age, with elementary school students much more likely to eat breakfast than loftier school students, and Black girls much less likely to eat breakfast than White girls.[xli] Information technology is estimated that approximately 25 percent of high schoolhouse students exercise not eat breakfast, a number that has been increasing over fourth dimension. A study of Minnesota high school students institute that the most common reasons for skipping the meal were students were likewise busy or didn't have enough time to eat breakfast, or they were not hungry in the mornings; 15 per centum of students worried that eating breakfast may cause weight gain.[xlii] Given the positive findings related to the SBP, these findings are worrisome and propose that overall academic operation could rise if the SBP reached these students who are not eating breakfast.

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4825869/

A study from 2009 found that students were more than likely to eat breakfast when it was served in the classroom and when more fourth dimension was provided for breakfast at school.[xliii] Research has also shown that students are more than likely to consume breakfast at school when it is universally available for free, not just to those with low income, largely because it reduces the stigma that children feel.[xliv] While the decline in SBP participation following the emptying of universally costless meals was greatest amongst students not otherwise eligible for a subsidized meal, participation too dropped by vii per centum amongst students who were eligible for a free or reduced-cost meal.[xlv] Similarly, when a universally gratis repast policy was newly adopted, participation among students who had already been eligible for a free or reduced-priced breakfast increased thirteen.one percent and 22.eight percent, respectively; participation amidst students paying full price increased 28.3 pct.[xlvi]

Another barrier limiting educatee participation in the SBP is the lack of availability. Schools are somewhat less likely to offering breakfast programs than luncheon programs: Only 85 percent of schools provide breakfast, while 91 pct of schools participate in the NSLP.[xlvii] Ane likely reason for this discrepancy is that the reimbursement charge per unit for breakfast is $0.78 less than the toll to provide it, while the loss on lunches is nearly 60 percent less at $0.32 per meal.[xlviii]

Conclusion

Overall, the NSLP and SBP piece of work to reduce nutrient insecurity and obesity and improve educational accomplishment. While older studies were less probable to observe positive health impacts of the programs, specially regarding the NSLP, studies conducted later implementation of the revised nutritional standards adopted in 2010 generally testify positive (or at least neutral) impacts, especially for lower-income individuals. The SBP was more consistently plant to yield positive wellness impacts, both earlier and after the nutritional standards were revised. Further, those early on studies that did find negative health impacts of these programs indicated such findings were likely correlated to a number of other factors based on students' income level. Equally for the educational benefits, the research more than strongly indicates the positive impacts of these programs. Research suggests that policy targeting pupil nutrition, particularly through the increased provision of breakfast, may be ane of the more cost-effective policy approaches to ameliorate student learning outcomes and test scores.

[i] https://www.mathematica.org/news/school-meals-are-healthier-after-major-nutrition-reforms

[two] https://frac.org/programs/national-schoolhouse-lunch-programme/benefits-schoolhouse-lunch

[3] https://world wide web.americanactionforum.org/inquiry/food-insecurity-and-food-insufficiency-assessing-causes-and-historical-trends/

[iv] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4892290/, https://world wide web.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2809930/

[v] https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns-hopkins-childrens-heart/what-nosotros-treat/specialties/nephrology/programs-centers/obesity-hypertension-clinic/_documents/eating-right-wake-upward-benefits-breakfast2.pdf

[vi] https://world wide web.sesp.northwestern.edu/docs/publications/982412224551ec93458609.pdf, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20648913?seq=one

[vii] https://www.sesp.northwestern.edu/docs/publications/982412224551ec93458609.pdf

[viii] https://www.jstor.org/stable/40802085?seq=ane

[ix] https://kinesthesia.smu.edu/millimet/classes/eco7377/papers/millimet%20et%20al.pdf

[10] https://faculty.smu.edu/millimet/classes/eco7377/papers/millimet%20et%20al.pdf

[11] https://jandonline.org/article/S0002-8223(08)02051-viii/fulltext

[xii] http://www.econ.ucla.edu/people/papers/currie/more/sbp_june_15_2004.pdf

[13] http://world wide web.econ.ucla.edu/people/papers/currie/more than/sbp_june_15_2004.pdf

[14] http://www.econ.ucla.edu/people/papers/currie/more/sbp_june_15_2004.pdf

[15] https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20308/w20308.pdf

[xvi] https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20308/w20308.pdf

[xvii] https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20308/w20308.pdf

[xviii] https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/ten.1377/hlthaff.2020.00133

[19] https://world wide web.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00133

[xx] https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1255&context=econ_las_workingpapers

[xxi] https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/11/111110142106.htm

[xxii] https://www.maxwell.syr.edu/uploadedFiles/cpr/publications/working_papers2/wp203.pdf

[xxiii] https://www.maxwell.syr.edu/uploadedFiles/cpr/publications/working_papers2/wp203.pdf

[xxiv] http://bestpractices.nokidhungry.org/sites/default/files/download-resources/Summertime%20Nutrition%20Program%20Social%20Impact%20Analysis.pdf

[xxv] https://www.epi.org/publication/a_look_at_the_health-related_causes_of_low_student_achievement/

[xxvi] https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn2421

[xxvii] https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/breakfastforlearning-ane.pdf

[xxviii] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/05/03/how-the-quality-of-school-lunch-affects-students-bookish-performance/

[xxix] https://irle.berkeley.edu/files/2018/ten/Universal-Access-to-Gratis-School-Meals-and-Student-Accomplishment.pdf

[xxx] https://dspace.wlu.edu/bitstream/handle/11021/33948/RG38_Barry_Poverty_2018.pdf?sequence=ane&isAllowed=y, https://www.safeandcivilschools.com/enquiry/graduation_rates.php

[xxxi] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/ten.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00638.10

[xxxii] https://agricultureandfoodsecurity.biomedcentral.com/articles/ten.1186/s40066-016-0083-3

[xxxiii] https://www.brookings.edu/web log/dark-brown-heart-chalkboard/2017/05/03/how-the-quality-of-school-lunch-affects-students-academic-functioning/

[xxxiv] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/05/03/how-the-quality-of-school-lunch-affects-students-academic-performance/

[xxxv] https://www.maxwell.syr.edu/uploadedFiles/cpr/publications/working_papers2/wp203.pdf

[xxxvi] http://bestpractices.nokidhungry.org/sites/default/files/download-resource/Summer%20Nutrition%20Program%20Social%20Impact%20Analysis.pdf

[xxxvii] http://bestpractices.nokidhungry.org/sites/default/files/download-resource/Summer%20Nutrition%20Program%20Social%20Impact%20Analysis.pdf

[xxxviii] https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-112sres98is/html/BILLS-112sres98is.htm

[xxxix] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/ten.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00638.ten

[40] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/primer-school_breakfast_program_national_lunch_program/

[xli] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00638.x

[xlii] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/manufactures/PMC4825869/

[xliii] https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/wischoolbreakfast/files/2009/10/The-School-Breakfast-Program-Participation-and-Impacts1.pdf

[xliv] https://schoolnutrition.org/uploadedFiles/5_News_and_Publications/4_The_Journal_of_Child_Nutrition_and_Management/Fall_2016/BarriersandAdvantagestoStudentParticipation.pdf

[xlv] https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/D_Ribar_Changes_2013.pdf

[xlvi] https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/D_Ribar_Changes_2013.pdf

[xlvii] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46234

[xlviii] https://world wide web.americanactionforum.org/research/primer-school_breakfast_program_national_lunch_program/

Source: https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/health-and-education-impacts-of-the-school-breakfast-program-and-national-school-lunch-program/

0 Response to "Creedmoor Elementary School of the Arts Free and Reduced Lunch"

Post a Comment